Flows and spirals of pool and powers

we burn our trash, our clay, our cities, our people

I’ve been quiet on here for the past few months; at my best, I’ve been living, absorbing a trip to Japan fully into my bones, deepening my well of obsession with the place; at my worst, I’ve been doubting that sharing myself through the art of writing is a worthwhile pursuit. There’s a recent dose of grief, both in my personal life and due to the gen*cides in Gaza and Sudan too, that makes language hard to come by. I’ve decided to keep trying and to keep sharing, trusting that sharing myself, no matter the size of the audience, brings me closer to the world, and so it’s always worth it. Sharing your art is really all we have.

I recently put Another Place to sleep for the winter. This involved closing up the camper, bringing the wool blankets home, and building a big fire to burn the twig piles. We took down the kitchen tent, hopefully to be replaced with an outdoor kitchen structure next summer, and packed the rest of the camping supplies up for winter storage. My friend and I made wreaths from evergreens, juniper, and some little moss that looks like trees found around the ten acres, and I learned that the origin of a wreath is a crown. When pulling into the property on the last morning, we saw a single coyote resting in some tall grass near the front driveway. I stopped the car and we just looked at each other for a while; eventually, it trusted that I wasn’t a threat, and took off walking South, tail low, beautiful.

The property will get this toilet/shower combo come Spring! My girlfriend and I are starting on the building of the bathhouse this Winter, using valuable indoor space available to me (with power, heat, and running water…) in Detroit to frame out the structure before transporting it to Another Place for assembly in the Spring.

I feel clarity that I want a home, and am humbled by the understanding that getting one will be difficult. Yet having a home, within this path I’ve chosen, means it first has to be designed and then built, and I am a financially independent person who has few building skills and works a full-time job. I know it will take strategy to be able to afford, and I know it will happen because I’m stubborn and obsessed. Lately, I’ve been talking with a small company in Maine that specializes in strawbale panels, a new technology that’s attempting to bring the benefits of strawbale and clay+plaster building methods, often called “natural building,” to panelized form, saving cost and expanding accessibility. I’ve also learned of a company in the Detroit area that specializes in hempcrete, hempwool, and plaster application. I’ve begun the process of exploring building plans and talking with architect friends, as well as reading international building code and learning about construction loan options. The learning is endless but I’m excited to realize that after a few years of this, I’m feeling more literate about the landscape of land ownership in this country, about building, and less afraid of financing. I’m excited to share some of my ideas with you.

Lastly, my line is currently open for anyone who has questions about any part of this process. I love answering questions and sharing what I know, even if it’s still a small slice of available knowledge, and I believe sharing is a meaningful articulation of expanding access. I know that it’s particularly difficult to navigate the system as a single person without family wealth, so eventually, I’ll open up low-to-no cost consulting calls for others interested in this route of land stewardship and home-building. I want to prioritize consulting for historically marginalized people, particularly LGBTQ+, people of color, and people displaced from this land I’m now on.

As always, thanks for being here.

Teshima Island, a small island of 700 residents off of the coast of the Kagawa Prefecture in Japan, labels their waste “burnables” and “plastic or cans” — some residents add a third category, “for the chickens.” The trash, as the category suggests, is burned. At first, this fact disturbed me. As an American, I’m familiar with my waste being removed from sight, incinerated or (what? what did I think?) buried in a landfill that children would someday play soccer on top of (my own experience playing on inner city parks & rec fields as a kid). Energy is neither created nor destroyed, so as long as trash is created by humans, the trash needs to release gas and turn into something else. The best answer is to use less, consume less, and create less trash, but for a world at-scale, that remains difficult. Japan is an archipelago in the sea and there simply isn’t space to create landfills that would support the trash of 125 million people. So the trash is burned. When I learned this, I thought of my friend who starts bonfires by burning all of his mail and paper trash, a method learned from his family in Northern Michigan. I thought of the smell of a burning house two blocks from my home in Detroit. My left wrist holds the scar of a hookah coal I couldn’t remove fast enough a decade ago. I thought of the time I threw oyster shells into a bonfire only to realize they explode with heat, shards flying at our heads. Where else can the trash go? On Teshima Island, our neighbor, an elderly woman wearing a big blue gardening visor, stood by the burning trash in her yard, poking it with a pitchfork, asking, I imagined, Where else can we go?

The ancient technique of noyaki is a sister of controlled field burning and a cousin of raku clay firing, first developed in the Aso area of Japan and practiced annually for the past 3000 years. In Tokyo, I saw two Japanese artists’ work, both inspired by noyaki and the history of clay. One piece by Japanese artist Nobuho Nagasawa, in particular, struck me. Nagasawa trained under prolific ceramicist Koie Ryōji, learning how to use the power of fire to make pottery. She used clay to build a large, sculptural structure, fortifying it by engulfing the structure in controlled flames for multiple days. Fire is unpredictable, and high winds caused them to extinguish the flames early, but still, the result was a singular fortified, charred mass, almost sentient in its texture.

The other artist, Tonoshiki Tadashi, invited community members from his hometown to collect beach trash that had floated across the Sea of Japan from Siberia. He filled a large pit with the collections, then lit the compacted trash on fire using a similar technique to raku, or pit-firing. The resulting mass was then pulled out using an integrated metal rod and flipped. I walked around the mass, now on the 74th floor of the absurdly lavish Roppongi Hills building in Tokyo, leaning in to see bottle caps, old beer cans, miscellaneous blue tubing, a rope, the hand of a doll, thinking, I’m learning what it was like to live in Siberia 40 years ago. The piece felt out-of-place in the clean art museum room but the air was filled with the sound of fire crackling, streaming out from a small TV screen on the wall, and I swear I could smell burning.

Noyaki is traditionally a “field firing,” essentially a controlled burn of grasslands to promote growth. In the land we call America, the tradition is ancient; in the area of Massachusetts there’s evidence of controlled burning techniques dating back 3000 years, showing a correlation between high burning years and an increased rate of chestnut tree growth1. These fires are necessary to promote growth, and though it sounds ironic, also necessary to prevent free-reigning wildfires. One plant, the manzanita shrub, native to the Western United States area up to British Columbia, only blooms when fire has passed over it (you can read a sweet ode to the manzanita by poet Gary Snyder here). Evergreens grow at a faster rate after a burning and with density that actually slows the spread of fire. In Japan, the tradition of burning is similarly ancient, originating in the Aso area to manage the mountainous grasslands for growing and food for cows. Interestingly, this area surrounds a massive active volcano, making me wonder if ancient people discovered the benefits of heat on their crops only after a tragic eruption. I imagine the tradition could have continued in America had indigenous people not been forced from their land, killed, and the practice of controlled burns literally outlawed2. Now, it seems the parks service are recognizing the utility of this ancient practice and calling on Native communities to once again take up this practice to help prevent destructive wildfires, though controlled burning remains illegal in many areas.

Back on Teshima Island, the smell of burning filled the air. From the yuzu grove up the hill, I could see narrow plumes of smoke rising up from neighbors’ yards in both directions, hanging near the side of the mountain. It was supposed to rain later that day, and as I learned then, everyone burns their trash before it rains.

Since October 7, Gaza has been burning, at first by a horrific attack by the violent military organization Hamas on civilians of Israel, and more and more by brutal attacks by the Israeli and United States militaries on innocent Palestinian hospitals, schools, homes. Most of these homes are not made of clay, they don’t get stronger from the flames, and no home could withstand the force of what some are saying is equal to the destruction of two nuclear bombs. People are burning, and the city that once was there no longer exists. I can hardly imagine the horror of losing Everything. I grew up in a white, Catholic, Midwestern house where there was very little, if any, talk of the ongoing war and violence in Gaza. Despite how far I felt from this violence while growing up, it continues to effect all of us. I feel deep support for the end of violence toward the innocent people of Gaza and an earnest wish to end Anti-seminitism and Islamaphobia or ethnic hate worldwide. The complexity cannot be reduced, but I feel certain that the destruction of one group will not heal or exact the crimes and destruction of another. Free Palestine, end the violence for all, end the war.

In Southeast Michigan, a man named Dave practices the ancient indigenous practice of field firing, or prescribed burns, with his company, Restoring Nature With Fire. One day before a burn is set, he sends out a group text to his crew — a medley of old firefighters, environment studies grad students, bartenders, and factotums in the area — with the location of the next day’s fire. Last spring and early summer, my girlfriend was on this crew, participating in several prescribed burns from Chelsea to Detroit. Fire is fickle, and a burn can’t happen on a windy day, or a day that’s too hot, or a rainy day. So the texts are sent the day before and require a simple response: I’m in. The crew meets at a common parking lot early, by 8am usually, and drives to the burn site together in Dave’s truck, its cabin lined with drip torch tanks, axes, orange fireproof suits, face shields, and first aid supplies. Usually, the burn site is a city park or private grassland on at least 80 acres. For a physically grueling 10-12 hours, the crew draws fire into the landscape with a drip torch, carrying 40lb backpacks of water on top of orange fireproof suits, making heavy steps with lug sole boots. Most people don’t wear masks because they don’t effectively block the smoke, though everyone really should be wearing a respirator. It’s a physically challenging job in every element: smoke pools around you burning your eyes and lungs, the sun beats down on you, some land requires trudging through marshland for hours, and sometimes the crew walks over five miles for one burn, only to begin a second burn at 3pm. As the landscape dances with flames, another wall of crew, like an interconnected on-foot search party, seeks out the flames and extinguishes them with water. The work stops when the sun goes down, not a minute before. By that time, the ground is charred, blackened. Any lingering fire inside of a tree trunk or a stump is carefully extinguished. The ground is hot, puffy with gray ash.

It’s also beautiful; when else can you see the world on fire and feel the power of that element surrounding you with relatively little fear? It turns out, in this case, to not be total destruction at all. Two days later, new green shoots will already be found popping up through the carbon-rich soil. Vegetation will grow more plentifully, and some conifers and eucalyptus will seed only when they’ve received a blast of heat.

This process in botany is called serotiny (and in this definition with fire, pyriscence3). While some trees and plants seed annually, most in our region require a change in order to release seed, likely an ancient species adaptation developed to increase the likelihood of successful reproduction; trees, like humans, are trying hard to survive. Serotiny means ‘to follow’ or ‘later’, reminding us that change is inevitable, and there is always the promise of After.

Sometimes an ending isn’t through destruction or a burning down. Endings can taper, gradually, indistinguishable from life itself. An illness can make fireworks of an ending or it can be quiet; one morning it is like that, now, so soon after, it is like this. We burn. This past week, I attended a graveside ceremony where family members set single stems of flowers atop a box of ashes, marking an end of life. A controlled burn ends everything around it in order to allow the old plants to grow new shoots. A raku firing burns clay until it fortifies, and hundreds of years later I behold it behind glass in a museum, the bowl lifted from its home buried deep in the ground for this purpose, my hands clasped behind my back as I pause to notice its beauty, trying to let the feeling of wonder, of that’s incredible, well up big enough inside of me to match the years it took for me and that bowl to meet. I can never quite get there. I can never quite match my pace with the endings, and yet we meet again and again.

We thrash and fight to add rationality to horror, yet violence isn’t rational. We have to resist, we have to fight, and we have to grieve, somehow all at the same time. Life is requiring impossible things from all of us right now. When it all seems impossible, I remind myself these words:

I can’t do it, you say it’s killing

me, but you thrive, you glow

on the street like a neon raspberry,

You float and sail, a helium balloon

bright bachelor’s button blue and bobbing …

(from “To have without holding” from Marge Piercy’s book, The moon is always female)

What I’m reading, listening to, thinking about

This post’s title taken from Gary Snyder’s poem, Burning Island

Thinking in Systems, a wonderful primer book on thinking about systems (everything on this planet, including our human relationships, are interconnected systems). I’ve found it helpful to zoom out in this time of conflict by zooming in to systems.

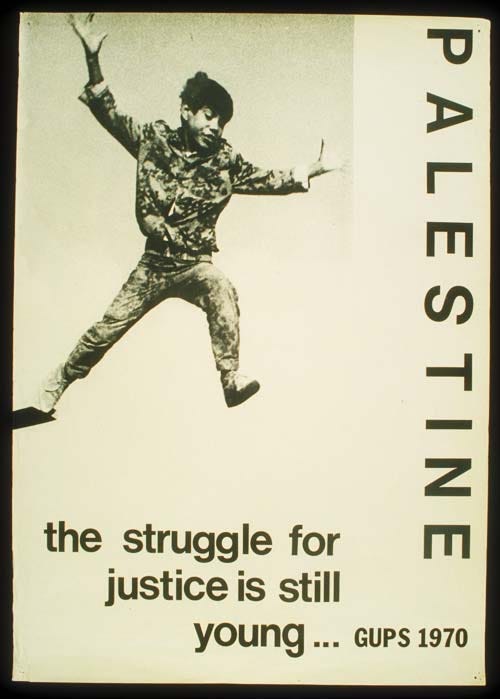

Palestinian resistance posters post by Nicole Lavelle’s newly launched newsletter PILES

Angela Davis on Black Lives Matter and Palestine (this is a free PDF of their book Freedom is a Constant Struggle), a pocket-sized book that has been by my side since June 2020 and the Black Lives Matter protests. More relevant than ever/always relevant.

My girlfriend makes beautiful paintings with the ash she collects the day after a controlled burn

Source: https://esajournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/ecs2.3267

The Weeks Act in 1911 largely outlawed Native American fire management and called for fire protection efforts through federal, state, and private cooperation. That didn’t work.

From this Wikipedia page: The passage of fire, however, reduces competition by clearing out undergrowth, and results in an ash bed that temporarily increases soil nutrition; thus the survival rates of post-fire seedlings is greatly increased. Furthermore, releasing a large number of seeds at once, rather than gradually, increases the possibility that some of those seeds will escape predation. Similar pressures apply in Northern Hemisphere conifer forests, but in this case there is the further issue of allelopathic leaf litter, which suppresses seed germination. Fire clears out this litter, eliminating this obstacle to germination.

~* Fire, bringer of life. Fire, bringer of death. Fire as destroyer. Fire as transformer. End, transition, & beginning. *~

Amazed to read this after having just returned from a pilgrimage to Japan also contemplating/researching waste burning there, and navigating my long-running anxiety about trash-burning neighbors where I live (BC, Canada). (I should preface by saying that I've been greatly enjoying your newsletter, which I stumbled upon by chance just as your chronicling here began, and have found your sharings to be incredibly resonant. As it happens, I'm situated on the opposite end of a somewhat similar journey, preparing with a heavy heart to leave the home that my grandfather built 38 years ago, and the land that my partner & I have been stewarding for the past 6 years...)

The oscillation between the fear of increased wildfires and the reintroduction of controlled burning practices here is very active, but as with so many issues I usually find people grouped at the extremes, with too little dialogue bridging the two. Similarly, open burning is allowed in my rural area for part of the year, with laws constraining the types of materials burnt and the methods used to contain the results. However, there is close to no dialogue or educational efforts attempting to establish a shared understanding between the 'burn-anything-however' types and the 'burn-responsibly-properly' types.

I think to myself: Once upon a time, everything we burnt was made of natural materials and we were a smaller species with simpler tools... now, it's complicated, but we are slow to adapt/teach/learn. As a result, I have an elderly neighbor who sometimes unwittingly sends billowing fumes of toxic smoke across our garden and into our home, and chunks of half-burnt photos & who-knows-what drift onto the land like snow. Once, after he dumped the resulting ash along the property line, I watched a hummingbird mother sipping at the pile to replenish the calcium lost in egg production, hoping with an anxious heart that somehow she and her babies won't be too greatly harmed by what else is in there...

Anyway, not to go on too long about this issue (too much to unpack), but it is very close to my heart. And reading about incineration practices in Japan after visiting has added a great deal more nuance to my feelings about 'burnables'. Like controlled burning, when done the right way, I can see how my intuitive reaction to burning trash has been largely misguided in the grander scheme. It's certainly not as great as waste reduction, but given the realities of consumption in an industrialized world, it seems to be a necessary process (until *insert-sci-fi-miracle-technology*, of course).

Thank you for your thoughtful reflections :^) I'd love to also reflect further upon the clay/art aspect, but must rush off to preparations for a rather hectic week.

(Also, just... Japan! We are also slowly absorbing the amazing experiences we had there and feeling varying flavors of post-travel depression. Re-grounding at home has been good, but the imminent holidays are making the transition feel especially surreal.)

p.s. In a previous newsletter, I was delighted to see your mention of Hideyuki Hashimoto's music, which I've been steeping myself in ritualistically for the past decade. Life-saving, really.

p.p.s. It occurs to me that I have a friend (& inspiration) in Michigan who writes in a similar spirit to you... perhaps, possibly you know/of him: https://cscottmills.com/about/ ? Seems like you two would resonate ~