Returning to a place after 20 years

Grief, visions, and staying with the trouble

Another Place Times is a regular newsletter about my land project in Northern Michigan, documenting the process of design+build projects, land regeneration, water, being queer in a rural area, and what it looks like to grow in a climate refuge. In my first post, I shared a bit about what you can expect from this newsletter. You can read that here.

Thank you to everyone who’s subscribed so far; it’s unbelievable and heart-warming. Living out in the open in the form of a newsletter is nerve wracking, and will inevitably be imperfect. Such is everything.

If you haven’t yet subscribed and want to keep reading, hit that free subscription button. If you are able to support, please consider becoming a paid subscriber ! As always, there is no pressure to support in paid forms. If you’d like to subscribe to all of it but can’t afford it, please reach out and we’ll find a price that works for you. <3

Lastly, please share with anyone you think would like this.

I’m beginning this newsletter with the story of how I ended up with 10.6 acres of land in Northern Michigan; on the TV this is the “you’re probably wondering how I ended up here, 3000 miles from home in a hot air balloon with Spike Lee” format. I’m breaking the story into a couple parts, of which this is the first.

Before launching into a fairly long story, though, I’d like to begin with one possible vision for the property:

One vision* 10 years from now, as you (reader) arrive at the property:

The driveway is gravel, visible from the road through an entrance of white pine, cypress, and a low hill running along the road, blanketed in milkweed, big bluestem tall grass, yarrow, aster, and goldenrod. It’s colorful and wild. You know you’ve arrived by the mailbox: a largemouth bass with an open mouth for the mail. You wonder if the cabin here also has a singing Big Mouth Billy Bass and you find out later that it does. You’re pulling into the driveway and you turn down the radio and open the window to hear the slow crunch of your car’s tires on the gravel. To your right, you see a small cedar shake workshop/garage/apartment. Inside the open doors, the artist-in-residence is making an 8ft tall paper maché puppet that looks a lot like Steve Carrell in the classic film Evan Almighty but you can’t place how - maybe the beard?, and you wave as you pass, heading further back into the property to the cabin where you’ll be staying. On the drive, you pass a small field of wildflowers with names you don’t know, and a lush garden of raised beds full of alive things. The air smells like tomato plants, hot sand, pine, and wood smoke. You think ‘that would be a good candle’. To your left is a small shed, and up ahead, just beyond the garden, is the cabin. It’s small, but the big window in the front lets in the south sun, and the diamond-shaped window in the loft lets in the breeze. The deck extends out on two sides, and you have the option to sleep in the loft, or out in the treehouse at the edge of the woods. The interior of the treehouse is painted the color of the night sky 30 minutes after sunset and it feels like sleeping in the belly of a whale. Back at the cabin is an outdoor shower and the sauna, which you probably won’t use because it’s July, but you never do know.

You stop your car and step out. Your 200lb Irish wolfhound, Dyper, has been in the backseat the entire time and now he jumps out and bounds around, immediately busy with a backlog of smells to inventory. Over the next few hours, everyone will arrive and you’ll begin cooking. Elle will emerge from the woods covered in moss and riding an off-road utility vehicle, and soon there will be a long table in the meadow behind the cabin and the sun will get lower and the air will cool, releasing the green, verdant, lush smells of Northern Michigan in late July. In the morning, you’ll go to the lake and someone will mistake your dog Dyper for a wizard.

*This is one of endless variations of visions for this place. It’s important for me to note that this place will inevitably be composed of everyone who visits it, everyone who reads this newsletter, and everyone who comments/reaches out to me and thus gives me something new to think about. It’s this co-creation that really fortifies my bones. I want this place to be a representation of participation on all levels, and I plan to extend many opportunities to share in this vision.

Let the wild rumpus begin1.

I’ve always seen life as something to record, to archive, to collect, and to research. If I remembered to bring a sharpie, I’d probably write more poetry on bathroom stalls. I’ve carved my name into a lot of picnic tables. I want to hear others’ stories and share my own so that someday, as long as a giant space magnet doesn’t scatter these digital words, someone can know I was here. Something tells me that’s the way, because a combination of my grandfather’s boxes of Kodachrome film slides, my dad’s journals, and my family’s oral histories led me here.

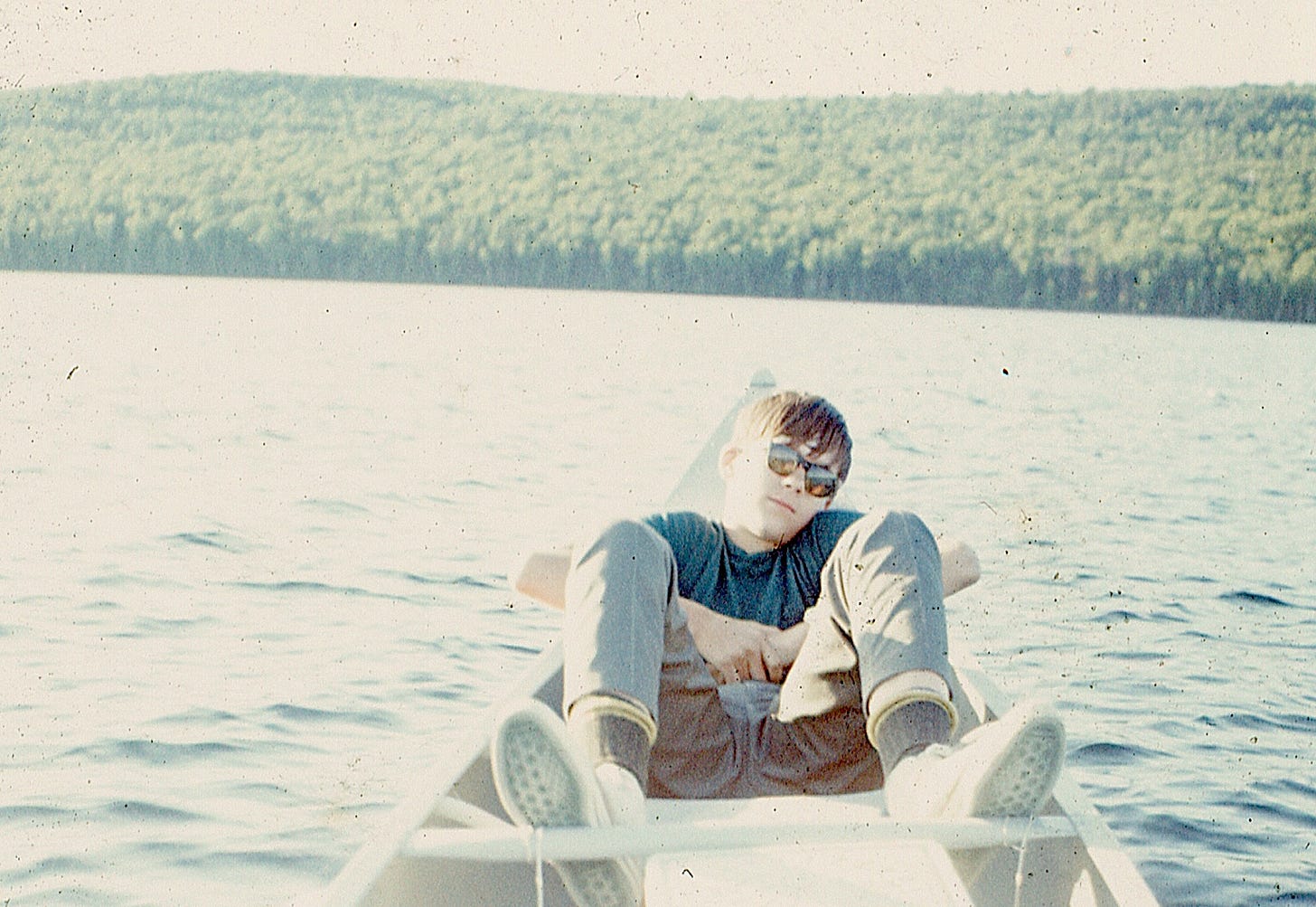

In 1963, my grandpa Robert (pictured below, grimacing toward the camera), along with four other men and their families, purchased 300 acres of land surrounding the Betsie River. My grandpa’s Mt. Pleasant fabric store, “Gover City Fabrics,” was thriving at the time, many years before Kmart would move into town and swiftly put them out of business. That fabric company started as a grocery and general store, opened in 1886 by my great, great (? thank you free ancestry.com) grandfather George, a young émigré from London, England. One hundred or so years later, Gover City Fabrics closed their doors.

Back in the 1960s, my grandpa and the other guys called their group the “Betsie River Recreation and Conservation Corporation LLC.” I imagine they named it this in jest because it takes so long to say. They laid a small concrete pad for an Airstream trailer, and for years they brought their families up to camp, went up solo to fish and drink too much beer, and canoe the wider rivers nearby.

A few years on, they collectively built a small cabin on a high point in one bend of the river. My dad, Mark, somewhere around middle-school age, his younger brother Gary, and kids from the other four families helped where they could. They painted it red and called it “The Place.”

This place grew with my grandparents, my dad, and his 3 siblings. It expanded from a simple concrete pad for a trailer into a small cabin. The building projects stopped there, but it became home for my dad, as he grew older and went to a well-known music school nearby.

He spent his last year of high school at Interlochen Center for the Arts, playing drums and keys in bands and applying to music schools, ultimately choosing the one closest to home. When he and my mom met in their early 30s, he shared The Place with her, revealing the deep ravine where my grandpa threw his beer cans (the conservation group had shaky bylaws), and showing her how you could see the same group canoe by an hour later by walking twenty feet from one bank of the river to the other. The land was left to grow, the cabin taking up a small amount of space in a mostly wild Michigan forest, the Betsie flowing on & on.

I loved going to the cabin. Our townhouse back home felt too small, the noise of a southside Lansing housing project was constant, and the green space limited to an open courtyard within the buildings. It was clear to me, even as a small kid, that The Place held significance for my dad. He was happier there; the image of him content in this place lodged itself deep into my heart, only making itself known years later as I tried to replicate that feeling. The Place held a quality for me that has never decomposed. Christopher Alexander, in his book “The Timeless Way of Building” calls this, “the quality that cannot be named,” composed, in part, of the quality of “aliveness.” The Place feels alive, and I recognize my own aliveness when I’m there.

Once when I was young, my mom claimed that she opened the oven and saw a family of mice dressed in colonial garb sitting down to a candlelit dinner, an almost mirror-image of our own family minus the doilies. I don’t remember us ever using the oven again, and she still tells this story as stubborn truth. A blue racer snake with the government name of ‘Blue’ lived under the porch steps, and our closest neighbor was a sweet man in his nineties with 3 remaining teeth called Dee, who allegedly would sit with me when I was a baby and hold my hand, just like that for a while.

In 2001, my dad and his siblings decided to sell The Place and its surrounding acreage. Money was tight for several of them, and at the time, the difference of a year’s worth of income and access to The Place was significant. The decision was made out of necessity and echoed with big regret. I remember sitting in the front passenger seat of my mom’s blue minivan and sobbing, one of the first big losses in my life. The Place held my imaginings, all the open space, the river, and, I knew, it held my dad.

In 2006, my dad died suddenly, taking his experience of The Place and much of its history with him. I was thirteen at the time, and this tragedy and grief ran my life for years; I liken it to the feeling of, in Kauai on my thirteenth birthday just three months before he died, hitting a big wave and being sent underwater, spinning and spinning with no concept of “up” until finally I was surrendered to air again, dangerous inches from a rock and my water shoes nowhere in sight. Freshly thirteen on that beach, I didn’t know then that the turbulence would continue.

I didn’t think about The Place for years, and this story essentially turned to static until 2019. In college, I’d become close friends with a few people from Northern Michigan, which brought me to the Benzie County area to spend holidays and summers at their childhood homes. On one of those trips, I realized we were under five miles from where The Place sat. I knew it when I passed one particular gas station on the corner and my body clicked with recognition: a million left turns past that station, then a million rights, then countless slow drives through the mile-long two-track to the cabin and the river, branches snapping against the top of the van, ushering us in.

I developed a dream of finding the cabin just to see it again. At that point, I had an idea that if I could see the cabin again, I’d feel that quality that can’t be named, and through that, I’d feel my dad. This dream came at a time when I was feeling particularly disconnected and groundless; it began as an attempt at connection and recollection, as desperate as that sounds. I started to let my mind wander around these questions: could it be possible to buy back the cabin? Could I regain what I’d lost? Could I, through buying the cabin back, connect the fragments of loss and through that, connect to an idea of family?

This dream required detective work, and through that, an unexpected and delayed process of grieving. What I didn’t know, but perhaps felt myself hurtling towards, was some actionable way to understand who my dad was, now that I was an adult. In some subconscious part of my brain, I knew that connecting with this place he loved so much, where I saw him exist in a simple, joyful form, would connect me with him. What I also didn’t know was that through this search, I’d develop my own distinct relationship with the area and what it means to be here now.

Over the next three years I spent more and more time up north. I learned from friends who moved up to the Petoskey area, searched for properties entirely out of my price range, figured out how to determine a price range, asked people what I should be looking for, made offers that were rejected, and generally went deep into research, trial, and error. I knew nothing about buying real estate. I relied on the knowledge of others and asked a lot of questions. I felt overwhelmed about the entire process, and then slowly, through time, built up my own library of knowledge and relationships in the area. I’ll talk about that process of searching & buying in the next newsletter.

This idea of ancestral legacy had me in its grip for years; I wasn’t willing to let go of the vision. I spent years trying. And then this property within one mile of my family’s old spot came onto the map, and all the work I’d done, a bit of good fortune, and privilege finally connected. This property is a testament to that stubbornness, and to dreaming as a valuable skill. It’s a connection to my family, for sure; the closing date was coincidentally the same week as the 16th anniversary of my dad’s death, a date that holds weight each year. But through the process, it took on its own magnetic form.

As of October 21, 2022, I legally own2 10.6 acres of the most beautiful, rolling dune land in Benzie County — one mile as the crow flies from where my family’s cabin still sits. The land is flat and clear in some parts with rolling hills of jack pines, white pines, and black locust in others. There are a couple acres of maple forest on the southern edge which will be tapped for maple syrup in a few years, and a lookout hill on the west side that lends a clear view of the local ski mountain. Eight miles west is Lake Michigan and Arcadia Dunes. Five miles east is Iron Fish, my close friends’ farm distillery. There is no structure on the land, which means no driveway, which means no electricity, water, or place to sha**.

It’s grown far beyond a reach for ancestral connection, into Another Place. It has become a place of my own, separate from my dad in important ways, and forever connected to what he and his family began. The process of finding it, of understanding financial barriers, of managing my own time, money, and education, to remain persistent and patient was possible because of the relationships in my life. Every time I flopped facedown, crying and discouraged, someone would be there to remind me of the myth of urgency and of the importance of gentle persistence.

In January, I was laid off from my job, which prompted an existential hemorrhage. I’ve since emerged from that spiral with many things illuminated, to the point where I now believe being laid off was the best thing that could have happened in my life at this time (highlighting that I have the privilege of being a singular person with no dependents, which greatly impacts this perspective). The truths in my life suddenly stood out in spotlights: friendship, love especially through the ugly times, learning through collaboration & community, and creative output. I was given the gift of sharp focus on what matters to me, how I want to spend my energy, and what isn’t worth my time. In a gasp, I began to live differently.

And still, I find myself caught within superficial orbs hanging on from the past few years, which has often felt less like a life and more like a gay apocalyptic multiplayer Sims game with four walls and no exterior doors: the fear, periods of endless rejection around buying property, the email notifications, the playlists, the worry of relevance, the bursts of attention or inattention, the attempts to anonymize and the yearning to be perceived. It all adds up to a central, begging question: do I exist?

Recently, I’ve returned to a truth: When in Another Place, I remember myself. This is a grounding, centering place.

Human made systems like social media rely on fragmentation, scarcity, hate, broadcasting, personal branding, jealousy. These systems and the — often subconscious — decisions they prompt burn fast and die hard, and also have lasting effects. Of course, there are beautiful chances for connection within social media. Some of my great loves began on the internet! I’ve been inspired by builders and makers through blogs. I’ve become part of queer communities and music blogs before I had those types of connections in any physical spaces. I’ve laughed at a lot of videos. The internet can remind me how much I love people.

However, addictive systems around social media in particular all become so deeply entangled in an intangible space that makes it difficult to distinguish real, physical connection from our imagery, perceived value, and worth as people. Beyond that, and most importantly, it makes it even more difficult to understand and see clearly other species’ worth, landscape’s worth, ecology’s worth. It makes it nearly impossible to focus on the space that’s all around us.

There’s only one way I know how to become in tune with that space, and that is to remove myself from the fizzling simulations online and to instead immerse myself in the physical world, turning towards ancient processes of seasons, tides, decomposition and new growth, connection with both land and people. In “Staying With the Trouble,” ecofeminist scholar Donna Haraway writes, “Staying with the trouble means making oddkin; that is, we require each other in unexpected collaborations and combinations, in hot compost piles. We become — with each other or not at all.”

In a different time, articulating that kind of sentence wouldn’t have been necessary; it seems so obvious. But truthfully, I need to remind myself of this often and I suspect many of you do as well.

I’m rushed with gratitude when I remember that Another Place will always be here. It is not a place that I rely on to make money. Its primary purpose is to exist and support all the life that’s already there, and I’m lucky to be able to find refuge in it. It has been there, long before white colonizers moved in and separated the land into straight-lines. That isn’t to say it will keep its current form; as we’re shown more and more by the day, landscapes are changing at exponentially faster paces. Climate change is in full-swing and has ravaged a majority of the worlds’ species, causing animals who have only ever lived in their own contained, circular ways, to go extinct. Land is becoming dryer, confused by intense, record-breaking swells of wetness that it can’t contain. The land called Benzie County has changed over the past twenty years, since I last meaningfully spent time here with my family, in ways that I’ll continue to learn as I meet elders and spend time. What we do know is that change is inevitable, and I’m calmed by that thought.

The vision I expressed at the beginning of this essay is borne out of questions, of which I have many constantly swirling through my mind:

Why is an artist there? Is there water? How can I best engage with the people who have lived here long before me? Will I be able to afford any of this? How can we be playful in a climate that is barreling toward destruction? In what ways can I introduce utility and pragmatism alongside absurdity and doing things for the sake of pure feeling? What does it mean to help facilitate resiliency? Will people visit?

One thing that feels bone-deep true is that this tactile life is what grounds me. Nearly everything else will fizzle as our environment roars on, one way or another. I cannot control most things, but I can make the decision to put my body here, to feel the place, to encourage it along and help make its natural processes easier (a farmer friend recently taught me a very metal restoration agriculture method called “STUN: sheer, total, utter neglect” <3).

I can make the decision to remember that nothing is more real than kissing my love on the forehead and stepping out of the camper in the morning, barefoot and thirsty and hit with the swirling, verdant scent of dirt dew, knowing that friends are on the way.

This is the area where I share what I’m inspired by

Ethical Futures by Cennyyd Bowles — a landmark text for me about implications of tech on our lives, possibilities for just futures, and general brilliant futurist thinking

Stolen Focus by Johann Hari — currently reading this about the loss of our individual and collective abilities to focus our attention; I highly recommend everyone read or listen to this book.

How to survive the end of the world with Autumn Brown & adrienne maree brown — this podcast has been a longtime inspiration to me, often citing Octavia Butler’s work.

In Service of the Wild: Restoring and Reinhabiting Damaged Land by Stephanie Mills — Mills, a legendary bioregionalist lives in the Leelanau Peninsula and has been doing regional work in ecologies, land restoration, and community-building for decades.

My friend Rowan put out new music

This Month — My friend Adam writes a monthly Substack sharing three (highly curated and opinionated) events around Detroit to go to each month

A quote from Where the Wild Things Are, a book that holds special meaning since my dad and his friend created a cassette-recording of the book read aloud with complete soundscapes and effects.

Owning property in any place, and especially a place where indigenous people were driven out through violence and inhumane lawmaking, is complex, and this is huge part of my learning journey as a new landowner.